Environmental Education: Part 4

– Strategies for Environmental Education from Philosophical Points of View

Jack Hiroki Iguchi (Professor, Graduate School of Environmental Sciences, Aomori University, Japan)

There are several arguments about environmentalism related to environmental education (Pepper 1984/1993, O'Riordan 1981). Definitions used by different authors differ slightly according to the ideological perspective, which can create confusion for the reader. However, two distinct ideologies can be commonly recognized (Job 1995). Job argues (Ibid) that these two positions can be regarded as a spectrum with "technocentric perspectives" at one end and "ecocentric perspectives" at the other. There is a close link between environmental ideology and the approach that is adopted to environmental education.

The technocentric perspective relates to an anthropocentric view of the earth in which the earth is regarded as a life support system predominantly for the benefit of human beings. This view of the earth proposes that the mechanisms of the earth's systems can be understood through scientific investigation and that the earth can be managed sustainably through the application of science and technology. On the other hand, the ecocentric perspective emphasizes that all living things, including human beings and non-living things, are equally vital to sustain the earth. A more detailed classification is given in figure 1 below.

SPECTRUM OF TECHNOCENTRIC & ECONCENTRIC PERSPECTIVE Fig 1

| | TECHNOCENTRIC | ECOCENTRIC |

| EARTH VIEW | MECHANISTIC / REDUCTIONIST | HOLISTIC / GAIANIST |

| UNDERSTANDING OF THE EARTH | SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION /ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT | SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION as well as SENSORY, EMOTIONAL SPIRITUAL WAYS OF KNOWING |

| RESOURCE DEPLETION & POLLUTION | TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS | CHANGES IN LIFE-STYLES

| | DEVELOPMENT ISSUES | LIMITING HUMAN NUMBER / DEVELOPING INDUSTRIAL TECHNOLOGHY | REDUCING CONSUMPTION IN RICH COUNTRIES TO ALLOW POOR COUNTRIES TO HAVE THEIR FAIR SHARE OF THE OTHER'S RESOURCES |

In addition, the technocentric perspective can be said to correspond with the philosophies of reductionism (complex phenomena are best understood by an analysis of components that breaks down the phenomena into their fundamental, elementary aspects – Reber S. 1985: 622); positivism (all knowledge is contained within the boundaries of science obtained by experiments or observations); materialism; and objectivism. This perspective relates also to quantitative analysis and hypothetico-deductive methodology (a scientific method that focuses on the deduction of hypotheses built up by the results of experiments or observations or known theories).

On the other hand, the ecocentric perspective mainly stems from Gaia theory (Note: a hypothesis devised by Lovelock J. in 1979; Gaia is Greek goddess of the earth), which says that the biosphere is like a single organism where all living things and non-living things are interrelated and is both self-regulating and self-organising (Jones G. et al, 1990: 186, Collin P.H. 1992: 94). This raises the question as to whether the harmful impacts of human activity on the earth will be corrected by self-regulating processes or whether Gaia will seek to sustain life in its broadest sense by eliminating the human species.

IMPLICATIONS OF ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY FOR EDUCATION

Most examples of environmental education include both tecnocentric and ecocentric perspectives. Fien (1992) describes three approaches to environmental education that he identifies as education "about", "through" and "for" the environment, each reflecting varying degrees of technocentric and ecocentric influence.

Education "about" the environment tends to reflect a technocentric perspective. This approach was the dominant form of environmental education especially in the 1970s (O'Riordan, 1981).

Education "through" the environment is to educate students through their experiences in the environment (Fien, 1992). "A fusion of education "about" and "through" the environment is characteristic of much common practice in the UK in outdoor education " (Job 1995), as in many field study centres.

Education "for" the environment is the ultimate end of the environmental education from an ecocentric perspective. It is seen in terms of promoting life-styles that will lead to a more sustainable earth. Fien (1992 quoted by Job 1995) summarized these three approaches to environmental education by suggesting that education "about" and "through" the environment are valuable only if they are used to provide skills and knowledge to support education "for" the environment.

AN ECLECTIC APPROACH COMBINING TECHNOCENTRIC AND ECOCENTRIC PERSPECTIVES (EATEP)

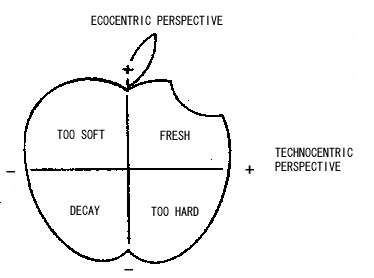

As any methodology of education has its own weakness, these approaches also have problems. The weaknesses of a purely technocentric approach are that it denies the validity of non-quantifiable forms of knowledge and experience; hypotheses generated by the hypothetico-deductive method are often narrow; reductionism fails to deliver a holistic landscape view; and it lacks the sense of uniqueness. On the other hand, the ecocentric approach can lead to unfocused studies in the field unless given suitable direction by teachers. These problems might be solved by using an eclectic approach combining technocentric and ecocentric perspectives (EATEP). EATEP emphases that in environmental education, tecnocentric perspectives must be balanced with ecocentric perspectives. Similarly affective learning is equally important to cognitive learning in order to enhance students' understanding and appreciation of the natural environment, which relates to ecocentric and technocentric approaches to environmental education. At museums, visitors' affective as well as cognitive learning have been regarded as important objectives in recent years. Historically however, as in environmental education through museums, the emphasis tended to be cognitive learning. The EATEP model is shown schematically in figure 2 below.

EATEP (An Eclectic Approach combining Technocentric and Ecocentric Perspectives) MODEL Fig 2

"How to bite a GREEN APPLE of ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION ?"

The next part in this series will examine environmental education in some European and developing countries.

Bibliography

Collin P.H., 1992. Dictionary of Ecology and the Environment, Peter Collin Publishing: 94.

Jones G.et al, 1990. Dictionary of Environmental Science, Collins: 186.

Reber A. S., 1985. The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology, Penguin Books: 622.

Fien J., 1992. Education for the Environment: Critical curriculum theorizing and environmental education, Deak in University Press, Australia.

Job D. A., 1995. Geography and Environmental Edcation – an exploration of perspectives and strategies, in Kent W. A., Lambert D., Naish M. & Slater F. (eds), Geography in Education, Cambridge University Press.

O'Riordan T., 1981. Environmentalism and Education, Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 5, 1: 3-18.

Pepper D., 1984. Roots of Modern Environmentalism, Croom-Helm, London.

Pepper D., 1993. Eco-socialism, from deep ecology to social justice, Routledge, London.

|