A Stronger Yuan Should Benefit not Japan but China Itself

Chi Hung KWAN (Senior Fellow, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry)

Led by Japan, major industrial countries are calling for the yuan's appreciation, saying it would help combat global deflation and correct their trade imbalances with China. However, for Japan, reflecting the fact its economic relationship with China can better be characterized as complementary rather than competitive, the overall impact of an appreciation of the yuan on the Japanese economy is likely to be a negative one. Led by Japan, major industrial countries are calling for the yuan's appreciation, saying it would help combat global deflation and correct their trade imbalances with China. However, for Japan, reflecting the fact its economic relationship with China can better be characterized as complementary rather than competitive, the overall impact of an appreciation of the yuan on the Japanese economy is likely to be a negative one.

The Chinese Yuan under Pressure to Appreciate

As symbolized by the rapid rise in China's foreign exchange reserves, the yuan is facing upward pressure. Boosted by rising inflow of foreign direct investment and exports, China's balance of payments surplus has widened further following WTO entry in late 2001. Reflecting this, the country's foreign exchange reserves rose $60 billion in the first half of this year to reach $346.5 billion at the end of June. This figure ranks second in the world behind Japan, and is equivalent to roughly one year's worth of China's imports.

Officially, China has a managed floating system, but ever since the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the yuan has remained stable against the dollar, and is virtually pegged to the greenback. If, as is the case now, the yuan's value is set at a level that is too low compared to its actual strength, dollar supply exceeds demand. When monetary authorities absorb excess dollars from the market, the nation's foreign exchange reserves increase as a result. If China were to adopt a floating system and authorities did not intervene at all in currency markets, its foreign exchange reserves would not have grown and the yuan would have appreciated instead.

If the authorities continue to keep the yuan at its prevailing level, China's trade imbalance and foreign exchange reserves will further increase, causing much harm to the Chinese economy. First, the surge in foreign exchange reserves will make it difficult to control money supply, and exacerbate the real estate bubble. In addition, China has already surpassed Japan as the country with which the United States has the largest trade deficit, and trade frictions have been rising as a result. Finally, most of China's foreign exchange reserves have been invested in US Treasuries, and since the return on those investments is much lower than that of investments made at home, it is clear that the savings of Chinese citizens are not being effectively invested. The yuan should be allowed to appreciate in order to correct such distortions.

In addition to adjusting exchange rates, reforms are also needed in the exchange system itself. First, against the backdrop of the sharp fluctuations in the yen-dollar rate and the fact that most Asian nations have shifted to a managed floating system, the yuan's stability vis-a-vis the dollar under the peg system causes large fluctuations in the exchange rate between the yuan and the currencies of its trading partners. This is a destabilizing factor for China's trade and its economy as a whole. At the same time, rising mobility of capital is making it more difficult to control money supply and interest rates, and the current de facto fixed exchange rate system should also be abandoned from the viewpoint of maintaining the independence of monetary policy.

Is Japan's Deflation "Made in China?"

Of the many countries calling for a stronger yuan, Japan is especially vocal. The Japanese government's line of thinking regarding the yuan issue can be seen in the opinion column titled "Time for a Switch to Global Reflation" jointly released in the Dec. 12, 2002, issue of The Financial Times by Haruhiko Kuroda, then vice minister for international affairs at the Ministry of Finance, and Masahiro Kawai, his deputy. In the column, they argue that the entry of Asia's newly emerging markets, such as China, into the global trade system is exerting strong deflationary pressure on industrialized countries, and that in order to resolve the deflation issue on a global scale, China's cooperation in further monetary easing and the appreciation of the yuan is necessary in addition to policy harmonization among Japan, the United States and Europe.

However, it is hard to believe that the China factor is greatly contributing to deflation in Japan. In 2002, Japan's imports from China accounted for a scant 1.5% of gross domestic product, and when the fact that the two countries compete very little on the trade front is taken into consideration, the effects of China-induced deflation on Japanese prices both directly and indirectly (through international competition) is limited. Furthermore, China's inflation rate (or, more precisely, its deflation rate) is at a level similar to that of Japan, and if China is to be branded as being the reason for deflation in Japan, then the opposite should also hold true.

For the sake of argument, even if deflation in China is accelerating deflation in Japan, is it really such a problem? To solve this question, we need to differentiate between whether the decline in the prices of Chinese goods is "good deflation" that leads to an expansion of production scale for Japan, or "bad deflation" that brings about a fall in output.

Needless to say, the Japanese media tend to focus on the "bad deflation" scenario. In other words, if the export prices of Chinese products fall, it is assumed that Chinese goods will take the place of Japanese goods, not only at home, but also in third country markets. This is deflation in the sense of its effect on prices, and it will also have a negative impact on Japan's output.

However, there is also a side to "Made in China" deflation that is "good deflation." In the case where a Japanese company imports various parts and intermediate goods from China, reduced prices of Chinese products signifies a drop in production costs, and as a result prices fall, but it is still of benefit to output.

The conclusion as to which of the effects – bad deflation or good deflation – is greater will differ depending on whether the economic relationship between Japan and China is viewed as being competitive or complementary. If the relationship is seen as competitive, the effect on the demand side will be greater, and there will be a larger negative impact. However, if the bilateral relationship is complementary, the positive impact on output will be greater because there will be a big effect on the supply side. When we look at the actual export structures of Japan and China, we see that the former focuses on high value-added high-tech products, while the latter concentrates on low value-added, low-tech goods. In other words, only a small part of their economic activities actually compete with each other, and because they are in a complementary relationship, the supply factors outweigh the demand factors, and for the producer, deflation in China is "good deflation" that brings about an increase in output.

Moreover, while the above analysis is based on the viewpoint of Japanese companies, for the Japanese consumer there is no need to differentiate between whether deflation is good or bad. For the public as a whole, just as in the case of a fall in oil prices, the decline in the import prices of Chinese goods means an improvement in Japan's terms of trade, and therefore an increase in real income.

A Stronger Yuan Will Do Japan No Good

By contrast, an appreciation of the yuan will likely have a negative impact on the Japanese economy through the "income effect," brought about by a deceleration of the Chinese economy, and the "price effect," caused by a surge in the prices of Chinese goods in international markets.

First, let us consider the income effect. If the yuan strengthens, the competitiveness of Chinese products in international markets will decline, and the Chinese economy, which is fueled by exports, will probably slow down. Yet, because processing makes up a great proportion of China's trade, Japan's exports to China will decelerate as a result. For Japan, whose export dependency on China is rising, this will be a big blow to such industries as the machinery industry.

Secondly, let us look at the price effect. The rise in the prices of China's exports will simultaneously apply upward pressure on both the input and output prices of Japanese industries, but the extent to which they will be affected depends on which has the greater impact on each individual industry. Generally speaking, in industries that compete with China on the output front, the greatest influence will be on output prices, and both profit and production will increase. In other words, the industries that would benefit from a stronger yuan would be limited to those labor-intensive industries in which Japan no longer has a comparative advantage. In contrast, for industries that are in a complementary relationship with China on the input front, the increase in input prices would be greater than that of output prices, meaning a decline in both profit and output. From the viewpoint of individual Japanese firms, companies whose products compete with those from China in both domestic and international markets will see their competitiveness increase with a stronger yuan, but companies that procure intermediate goods from China will be adversely affected through an increase in production costs.

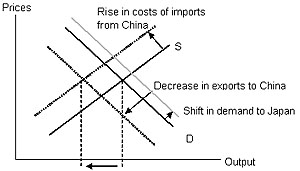

When considering the price effect of a stronger yuan on the Japanese economy as a whole, total output would increase (the demand curve would shift to the right) if a majority of industries were in a competitive relationship with China. However, in reality, there are more industries that are in a complementary relationship with China so that the negative effect on output is likely to dominate (because the supply curve shifts more sharply to the left). When the aforementioned negative income effect (the shift to the left of the demand curve) is also taken into account, a stronger yuan would have a negative, rather than positive, effect on Japanese output. Meanwhile, for the Japanese consumer, the rise in prices of Chinese goods signifies a decline in real income.

Diagram: Effects of a Stronger Yuan on the Japanese Economy

Thus both the diagnosis that China is the reason for deflation in Japan and the prescription that the situation can be corrected through a stronger yuan are wrong. As long as the real cause behind deflation in Japan remains the delay in structural reforms and the accompanying domestic economic slump, it is clear that unless such problems are solved, there can be no real economic recovery in Japan no matter how strong the yuan becomes.

(A Japanese version of this article appeared in the August 19, 2003 issue of "Weekly Economist")

|